When a patient comes in with unexplained abdominal pain, jaundice, or digestive issues, a pancreatic duct blockage could be the hidden culprit. This guide walks you through everything you need to know-from anatomy and causes to the latest imaging tricks and step‑by‑step treatment plans-so you can spot and manage this condition confidently.

Key Takeaways

- Pancreatic duct obstruction often presents with pain, jaundice, and elevated enzymes, but the pattern can vary by cause.

- High‑resolution MRCP and therapeutic ERCP remain the gold standards for diagnosis and intervention.

- Endoscopic stenting is first‑line for most benign obstructions; surgery is reserved for refractory cases or malignancy.

- Early recognition and multidisciplinary care reduce complications like infection or chronic malabsorption.

- Follow‑up imaging at 4-6 weeks post‑intervention helps catch recurrence before symptoms flare.

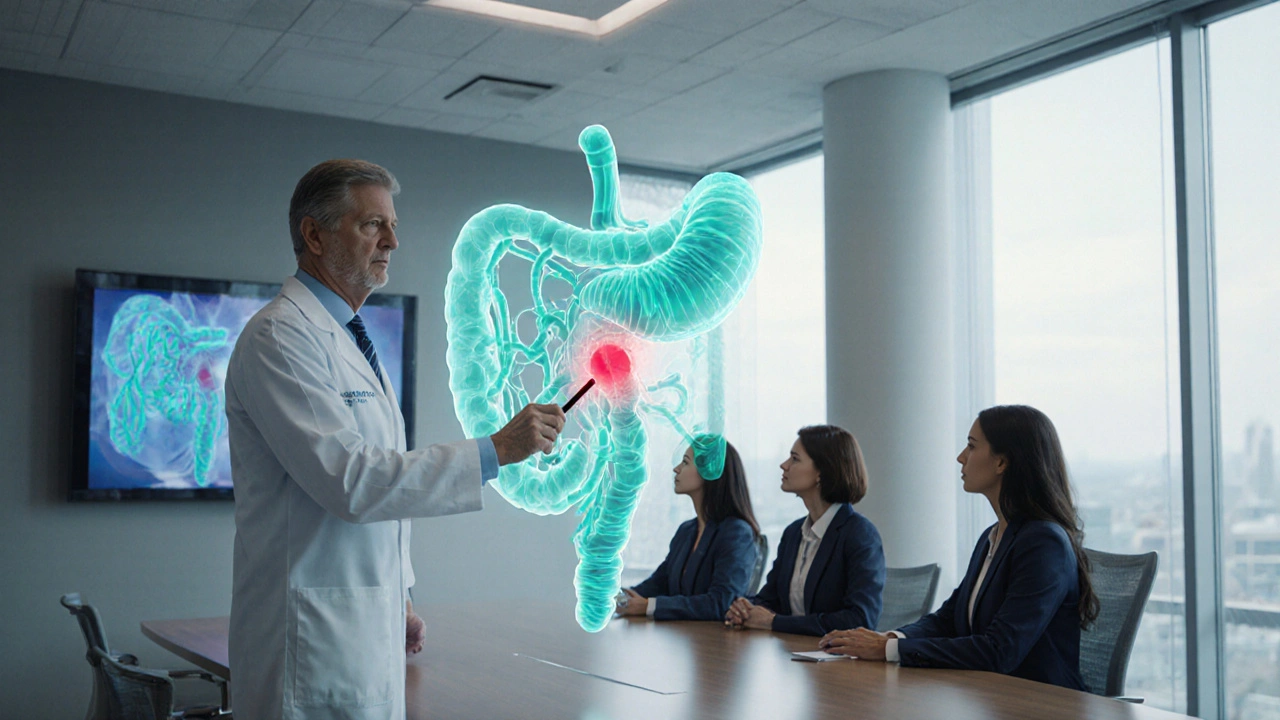

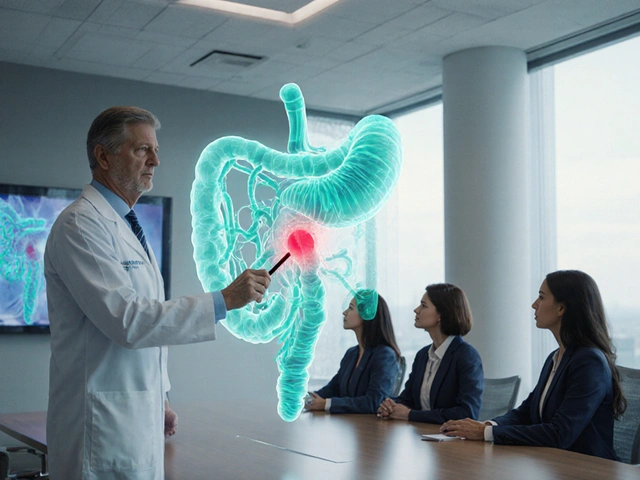

What Is Pancreatic Duct Blockage?

Pancreatic duct blockage is a condition where the main conduit that carries pancreatic enzymes into the duodenum becomes narrowed or completely occluded. The blockage can be partial, allowing some flow, or total, leading to a buildup of secretions inside the pancreas. This pressure rise triggers inflammation, pain, and, if untreated, irreversible tissue damage.

Relevant Anatomy

The pancreatic duct (also called the duct of Wirsung) runs the length of the organ and joins the common bile duct at the ampulla of Vater. It is regulated by the sphincter of Oddi, which coordinates the release of enzymes and bile into the duodenum. Any lesion along this pathway-stones, strictures, tumors-can impair drainage.

Common Causes and Risk Factors

Understanding why the duct gets clogged guides both diagnosis and treatment. The most frequent culprits include:

- Gallstone migration: Stones from the gallbladder can lodge at the ampulla, creating a functional obstruction.

- Chronic pancreatitis: Repeated inflammation leads to fibrosis and stricture formation.

- Pancreatic head tumors: Adenocarcinoma or neuroendocrine tumors compress the duct from the outside.

- Benign strictures: Post‑ERCP scarring or autoimmune pancreatitis.

- Parasitic infection: Rarely, helminths can block the duct in endemic regions.

Age over 50, heavy alcohol use, and a history of biliary disease increase the odds of an obstructive event.

How Patients Present

Symptoms vary with the level and duration of blockage:

- Epigastric pain radiating to the back-often worsens after fatty meals.

- Jaundice if the common bile duct is involved.

- Steatorrhea and weight loss due to malabsorption of fats.

- Elevated serum amylase and lipase, though levels may be modest in chronic cases.

Because these signs overlap with pancreatitis and biliary colic, imaging is essential for confirmation.

Diagnostic Workup

Start with basic labs, then move to high‑resolution imaging. Below is a quick comparison of the most useful modalities.

| Modality | Resolution | Therapeutic Capability | Typical Indications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transabdominal Ultrasound | Low‑moderate | No | Initial assessment, gallstones |

| Contrast‑enhanced CT | High | No | Evaluate pancreatic mass, necrosis |

| MRCP (Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography) | Very high, non‑invasive | No | Map duct anatomy, detect strictures |

| ERCP | High, with direct contrast | Yes - stenting, sphincterotomy | Therapeutic intervention, tissue sampling |

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is the preferred non‑invasive test to delineate obstruction. When you need to intervene-place a stent or obtain a biopsy-ERCP becomes both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Management Strategies

Treatment hinges on cause, patient stability, and available expertise. Below is a step‑wise approach you can follow in most hospital settings.

- Initial stabilization: IV fluids, pain control, and nil‑by‑mouth status if pancreatitis is suspected.

- Endoscopic therapy (first‑line for benign obstruction):

- Perform sphincterotomy to relieve the sphincter of Oddi pressure.

- Deploy a plastic or metal stent across the stricture. Plastic stents are cheaper but need replacement every 3 months; covered metal stents last longer but may occlude the pancreatic duct side‑branches.

- Percutaneous drainage (when ERCP fails or anatomy is altered): Image‑guided catheter placement can decompress the upstream duct and allow for subsequent elective endoscopy.

- Surgical options (reserved for malignant obstruction or refractory benign disease):

- Pancreaticojejunostomy (Puestow procedure)-creates a permanent bypass.

- Resection of a tumor when the disease is localized.

- Adjunct medical therapy: Enzyme replacement for malabsorption, antibiotics for infected fluid collections, and low‑dose somatostatin analogs to reduce secretions in select cases.

Choosing between plastic versus metal stents often depends on expected duration of blockage. For short‑term benign strictures, a 10‑Fr plastic stent works well; for suspected malignant compression, a fully covered self‑expanding metal stent offers longer patency.

Complications to Watch For

Even with expert hands, several downstream issues can arise:

- Post‑ERCP pancreatitis: Occurs in 5-10% of cases; prophylactic rectal NSAIDs reduce risk.

- Stent occlusion: Leads to recurrent pain; schedule routine exchange.

- Infection of upstream ducts, especially after incomplete drainage.

- Bleeding from sphincterotomy, usually self‑limited.

Early detection of these problems-via repeat labs or imaging-prevents progression to chronic pancreatitis or sepsis.

Practical Checklist for Clinicians

- Confirm the diagnosis with MRCP before attempting ERCP when possible.

- Assess coagulation status; correct INR >1.5 prior to invasive procedures.

- Administer rectal indomethacin (100mg) immediately before ERCP to lower pancreatitis risk.

- Choose stent type based on expected duration and etiology of obstruction.

- Schedule a follow‑up MRCP or CT at 4-6weeks post‑intervention.

- Educate patients on signs of infection (fever, worsening pain) and when to seek urgent care.

Future Directions

Newer technologies like endoscopic ultrasound‑guided pancreatic duct drainage (EUS‑PD) are gaining traction for cases where conventional ERCP is impossible. Early reports suggest comparable success rates with fewer complications, but widespread adoption will depend on operator expertise and device availability.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I differentiate a benign stricture from a malignant obstruction?

Imaging patterns on contrast‑enhanced CT and MRCP help-malignancies often cause abrupt cutoff with irregular margins and upstream atrophy. Tissue sampling during ERCP (brush cytology or fine‑needle aspiration) provides definitive diagnosis, though repeat sampling may be needed for false‑negative results.

When should I consider surgery instead of endoscopic stenting?

Surgery is indicated when stent placement fails repeatedly, when the patient has a resectable pancreatic head tumor, or when chronic pancreatitis leads to recurrent painful strictures despite optimal endoscopic management. Multidisciplinary tumor boards usually make the final call.

What prophylaxis reduces post‑ERCP pancreatitis?

A single dose of rectal indomethacin (100mg) administered within 30minutes of the procedure, combined with aggressive intravenous hydration, cuts the incidence by roughly 50% in high‑risk patients.

Can a patient with pancreatic duct blockage be managed conservatively?

Only if the obstruction is partial, asymptomatic, and not causing enzyme backup. Regular monitoring with labs and imaging is essential, and the patient should be advised to avoid alcohol and high‑fat meals that can exacerbate ductal pressure.

What are the latest stent technologies for pancreatic duct obstruction?

Biodegradable polymer stents are being trialed; they provide temporary patency and then dissolve, eliminating the need for removal. Fully covered self‑expanding metal stents remain the workhorse for malignant cases due to their longer lifespan and ease of exchange.

I completely understand how overwhelming it can feel when a patient presents with vague abdominal pain, jaundice, and digestive disturbances-it's like trying to solve a puzzle with missing pieces! Remember that early imaging, especially high‑resolution MRCP, can be a real game‑changer, and it’s absolutely crucial to coordinate with radiology early on. Also, keeping the patient informed about the steps ahead can greatly reduce anxiety, so never underestimate the power of clear communication! 🌟

MRCP before ERCP is the way to go.

Oh dear, if only every clinician could wield MRCP like a sorcerer’s wand, the pancreatic ducts would never stay hidden! 🎭 Yet, let us not forget the subtle art of interpreting the stricture’s morphology-only the truly enlightened can discern the whisper of a benign versus malignant tale. #MedicalMysticism

Spotting the pattern early saves a lot of trouble later.

Yes! Early detection is like catching a spark before it becomes a wildfire-keep that vigilance high and the outcomes will thank you!

Honestly, most of the so‑called "guidelines" are just recycled textbook drivel; seasoned gastroenterologists know that a well‑placed stent is all that matters, not endless checklists.

While the sentiment about checklists is understandable, evidence‑based protocols actually improve patient safety by standardizing critical steps. Numerous randomized trials have demonstrated that pre‑procedure rectal indomethacin reduces post‑ERCP pancreatitis rates by roughly half. Moreover, systematic follow‑up imaging at four to six weeks allows clinicians to identify stent occlusion before symptomatic recurrence. Ignoring these data in favor of intuition alone risks unnecessary complications. Therefore, integrating guideline‑driven pathways with clinical expertise yields the best outcomes.

One must appreciate the tragic elegance of a pancreatic duct obstruction-a silent assassin lurking behind nonspecific pain, poised to unleash devastation upon the unsuspecting organ. The clinician, armed with only imaging and acumen, stands at the precipice of decisive intervention.

Indeed, the balance between therapeutic benefit and procedural risk must be evaluated meticulously, employing validated scoring systems whenever feasible.

In the grand theatre of medicine, the pancreatic duct is a symbol of our nation's resilience-only the strongest will conquer its hidden adversaries, for we are the keepers of true healing!

When faced with a suspected pancreatic duct blockage, the first principle is to stabilize the patient with aggressive fluid resuscitation and analgesia.

Simultaneously, obtain a thorough history focusing on risk factors such as alcohol use, prior biliary disease, and recent episodes of pancreatitis.

Laboratory evaluation should include a complete metabolic panel, liver function tests, and pancreatic enzymes, noting that chronic cases may show only modest elevations.

Imaging should commence with a high‑resolution MRCP to delineate the anatomy without exposing the patient to radiation.

If the MRCP reveals a discrete stricture or obstructing stone, the next step is to plan therapeutic ERCP with a multidisciplinary team.

During ERCP, a careful sphincterotomy mitigates pressure at the ampulla and facilitates stent placement.

Selection of stent type hinges on the underlying etiology: a 10‑Fr plastic stent for benign strictures, and a fully covered self‑expanding metal stent for suspected malignant compression.

Prophylactic rectal indomethacin administered immediately before the procedure has been shown to halve the incidence of post‑ERCP pancreatitis.

Post‑procedure, monitor the patient closely for signs of infection, bleeding, or worsening pain, and obtain serum amylase levels at 24 hours.

Arrange follow‑up imaging, preferably MRCP or contrast‑enhanced CT, at four to six weeks to assess stent patency and detect early recurrence.

If stent occlusion is identified, schedule an exchange promptly to prevent chronic ductal hypertension.

In cases where ERCP fails due to altered anatomy, consider percutaneous transhepatic drainage as a bridge to definitive therapy.

For malignant obstruction not amenable to resection, systemic chemotherapy combined with stent palliation can improve quality of life.

Never forget to counsel patients on lifestyle modifications, including abstinence from alcohol and a low‑fat diet, to reduce further ductal stress.

Finally, maintaining a detailed log of interventions, imaging dates, and biochemical trends empowers the care team to make evidence‑based decisions and ultimately enhances patient outcomes.

Stents help keep the duct open.

While simplicity is appealing, omitting the nuance of stent selection overlooks crucial evidence and can jeopardize patient safety.

Sometimes the pancreas feels like a hidden conspiracy of enzymes, quietly plotting against us-yet with vigilant imaging we can expose the plot! 🕵️♀️

If we keep ignoring the signs, we're basically playing god with people’s guts-smh, that’s just not okay.

Remember, every challenge is an opportunity to refine your skills; stay focused, stay compassionate, and the team will follow your lead.

Indeed; meticulous adherence to the proposed checklist-comprising pre‑procedure prophylaxis, imaging timelines, and post‑procedure monitoring-constitutes a paradigm of best practice; consequently, patient morbidity is demonstrably reduced.

The protocol aligns with current NICE recommendations and should be adopted universally.

Totally agree, it’s great when the guidelines actually make sense in real life-keeps us from feeling lost.

In those quiet moments after a tough case, I find the quiet confidence of a well‑planned pathway truly heroic-keep shining, fellow clinicians!