Generic drugs make up over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., yet they account for just 17% of total drug spending. That’s not magic-it’s strategy. Insurers aren’t just hoping for low prices; they’re actively using bulk buying and tendering to cut costs, often saving millions per year. But how? And why do some patients still pay $87 for a generic pill when someone else pays $5 cash? The answer lies in who controls the system-and how they use it.

How Bulk Buying Works for Generic Drugs

Bulk buying isn’t just buying in large quantities. It’s about using market power to force prices down. When an insurer or pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) signs a contract with a generic drug maker, they don’t just ask for a discount. They say: "We’ll buy 10 million pills of this drug over the next two years-if you give us the lowest price you offer anyone else." This is called volume commitment. The drugmaker agrees because they know they’ll sell far more than they ever would selling one pharmacy at a time.

Think of it like Costco. You don’t pay less because the item is cheaper to make. You pay less because you’re buying in bulk. Insurers do the same with drugs like metformin, lisinopril, or atorvastatin. These are drugs made by dozens of companies. The more manufacturers competing, the lower the price. In fact, when three or more companies make the same generic, prices often drop 80-90% from the original brand price.

According to the FDA, the first generic version of a drug saves an average of $5.2 billion in its first year. That’s not a guess. It’s based on real data from drugs like lacosamide, pemetrexed, and bortezomib-each of which saved over $1 billion after generics entered the market.

Tendering: The Silent Auction That Drives Down Prices

Tendering is the formal process behind bulk buying. It’s like an auction, but backwards. Instead of buyers bidding up, manufacturers bid down. Insurers or PBMs issue a request for bids (RFB) for a specific drug class-say, all blood pressure medications. Companies submit sealed bids. The insurer picks the lowest price that meets quality and supply requirements. Contracts last 1-3 years. This creates predictability: insurers know what they’ll pay. Manufacturers know how many pills they’ll sell.

But here’s the catch: not all tendering is equal. Some PBMs use what’s called "spread pricing." They tell the insurer they paid $10 for a prescription. Then they charge the insurer $15. The $5 difference? That’s their profit. And guess what? They often pick higher-priced generics to maximize this spread. The JAMA Network Open study from 2022 found that many insurers had no idea which generics were driving their costs-and that some "generic" drugs were costing more than others in the same class.

That’s why transparency matters. Some insurers now demand full disclosure of pricing. California’s Senate Bill 17, passed in 2017, forced PBMs to reveal any price difference over 5%. The result? A drop in unnecessary high-cost generics.

Why Some Generics Cost More Than Others

Not all generics are created equal. A generic drug isn’t just a copy-it’s a product with a supply chain. If only one or two companies make a drug, competition disappears. And prices rise. The FDA found that in certain drug classes, just three manufacturers produce 80% of the supply. That’s not a market-it’s a cartel waiting to happen.

Take albuterol inhalers. In 2020, after a price war drove prices below production costs, manufacturers stopped making them. Result? 87% of hospitals reported shortages. Patients couldn’t get their medication. The system broke because it was built on squeezing profits to zero.

Meanwhile, some generics are priced high not because they’re rare-but because they’re hidden. PBMs often don’t disclose their Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists-their internal price caps for reimbursement. So even if a drug costs $3 to make, your insurer might only reimburse the pharmacy $10. But if the pharmacy charges $15, you pay the difference. And you never know why.

What Insurers Do to Avoid Being Played

The smartest insurers don’t just rely on PBMs. They do their own analysis. They look at quarterly reports. They track which generics are costing the most. They ask: "Is this drug really cheaper than the alternative?"

One health plan in Texas noticed that a generic version of a thyroid drug was costing twice as much as another generic with the same active ingredient. They switched. Saved $1.2 million in six months.

They also use therapeutic substitution. If two drugs work the same way, they pick the cheaper one. No doctor approval needed. It’s built into the formulary. This is legal, safe, and common. And it’s one of the biggest reasons why generic spending is so low compared to brand drugs.

But here’s the irony: 78% of Medicare Part D plans still put generics on higher tiers than they should. That means patients pay more out-of-pocket even though the drug cost pennies to produce. Insurers aren’t always saving patients-they’re just saving themselves.

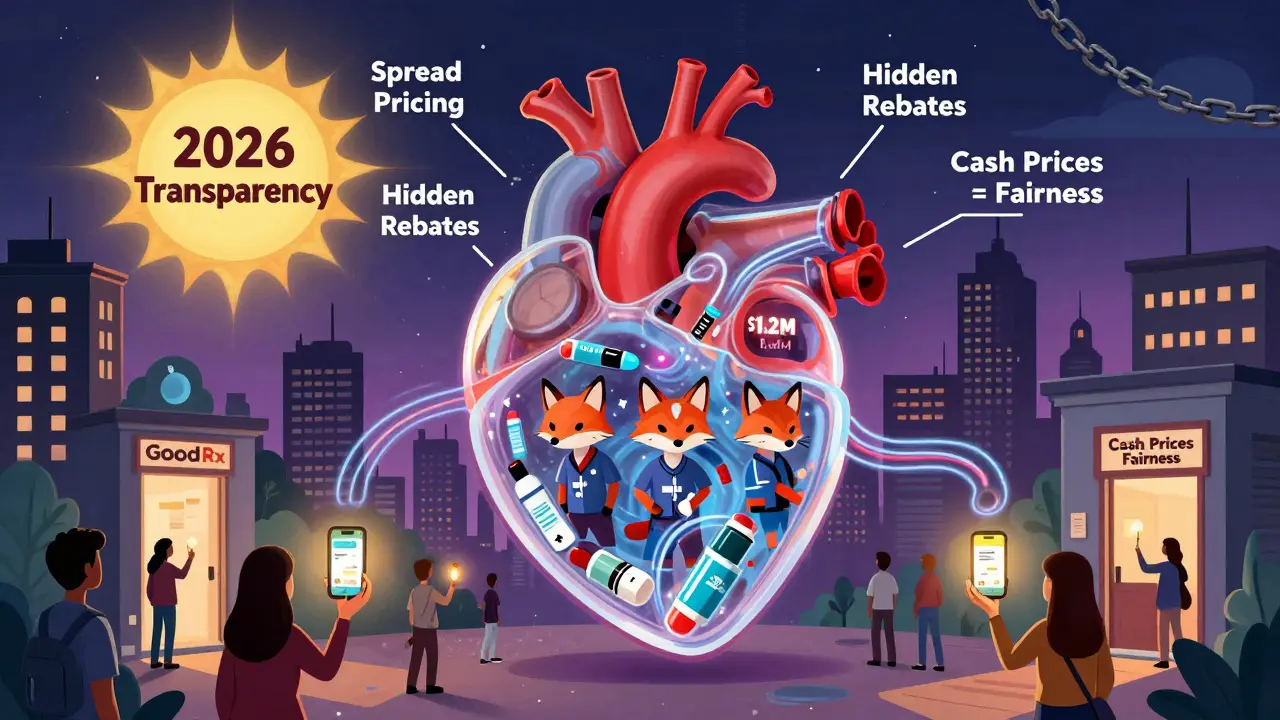

The Rise of Transparent Alternatives

When insurance doesn’t work, people go around it. That’s why cash prices for generics are often lower than insured prices. GoodRx, Cost Plus Drug Company, and Blueberry Pharmacy are growing fast. Why? Because they cut out the middleman.

Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company charges a flat 15% markup over wholesale. No spreads. No rebates. No mystery. A 30-day supply of lisinopril? $4.99. Amlodipine? $5.99. A statin? $10. Compare that to a typical insured copay of $25-$40. The savings? 75-91%.

A 2023 NIH study found that DTC pharmacies saved patients $231 per prescription on expensive generics and $19 on common ones. That’s not a coupon. That’s a system designed to work for patients, not profit.

Blueberry Pharmacy, with a 4.7/5 rating on Trustpilot, says: "No surprises. No insurance hoops. Just price." One user wrote: "My blood pressure med costs exactly $15/month. No more guessing. No more denial letters."

What’s Changing in 2026

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 didn’t fix everything. It capped insulin at $35 for Medicare, but left PBMs alone. Still, pressure is building. In January 2024, CMS required Medicare Part D plans to disclose how much they pay pharmacies and how much they charge patients. That’s a big step.

Meanwhile, the FDA’s GDUFA III program is speeding up generic approvals. More approvals mean more competition. More competition means lower prices.

And new models are emerging. Navitus Health Solutions, a PBM that works directly with employers, reported 22% lower generic costs in 2023 than traditional PBMs. How? They eliminated spread pricing. They used transparent tendering. They gave clients full access to pricing data.

The future isn’t about more regulation. It’s about more transparency. When insurers can see exactly what they’re paying-and why-they’ll stop overpaying. And patients will finally benefit.

What You Can Do

If you’re on insurance and paying more than $10 for a generic, ask why. Compare prices using GoodRx or SingleCare. Pay cash if it’s cheaper. Ask your pharmacist: "Is there a lower-cost alternative?" Your doctor can often switch you to a cheaper version without changing your treatment.

If you’re an employer or plan sponsor, demand full pricing transparency from your PBM. Require disclosure of spread pricing. Audit your formulary quarterly. Look for high-cost generics with cheaper alternatives. Use therapeutic substitution. Don’t assume your PBM is working for you.

The system is broken-but it’s fixable. The tools are already here. It’s just a matter of who’s willing to use them.

Why do some generic drugs cost more than others even if they have the same active ingredient?

Even when two generic drugs have the same active ingredient, they can cost differently because of how many manufacturers make them, where they’re produced, and how they’re priced by PBMs. If only one or two companies make a drug, competition drops and prices rise. Also, PBMs sometimes favor higher-priced generics because they earn more through spread pricing-charging insurers more than they pay pharmacies. So the drug isn’t more expensive to make-it’s more expensive to buy because of how the system is structured.

How do pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) affect generic drug prices?

PBMs act as middlemen between insurers, pharmacies, and drugmakers. They negotiate prices, manage formularies, and collect rebates. But many use "spread pricing," where they charge insurers more than they pay pharmacies and keep the difference as profit. This creates a hidden incentive to choose higher-priced generics-even when cheaper, equally effective options exist. Some PBMs also don’t disclose their Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists, leaving insurers and patients in the dark about true drug costs.

Can I save money on generics by paying cash instead of using insurance?

Yes, often. Many cash prices at pharmacies like Costco, CVS, or Cost Plus Drug Company are lower than your insurance copay, especially for common generics like metformin, lisinopril, or atorvastatin. In fact, 97% of cash payments in 2020 were for generic drugs, even though only 4% of all prescriptions were paid in cash. This shows that when insurance doesn’t offer value, people go around it. Tools like GoodRx can show you the lowest cash price in your area.

What’s the difference between bulk buying and tendering?

Bulk buying means purchasing large quantities to get a lower price per unit. Tendering is the formal process used to get that price: insurers or PBMs invite multiple drugmakers to bid for a contract. The lowest bid wins, often with a requirement that the manufacturer supply a minimum volume over a set period. Bulk buying is the goal; tendering is the method. Together, they create a competitive market that drives prices down.

Why do generic drug shortages happen?

Generic drug shortages happen when prices drop too low for manufacturers to profit. If a drug’s price falls below the cost of production-due to too much competition or aggressive tendering-companies stop making it. This happened with albuterol inhalers in 2020, when prices crashed and 87% of hospitals reported shortages. It’s a classic case of market failure: too much price pressure kills supply. The solution isn’t higher prices-it’s better balance between competition and sustainable manufacturing.